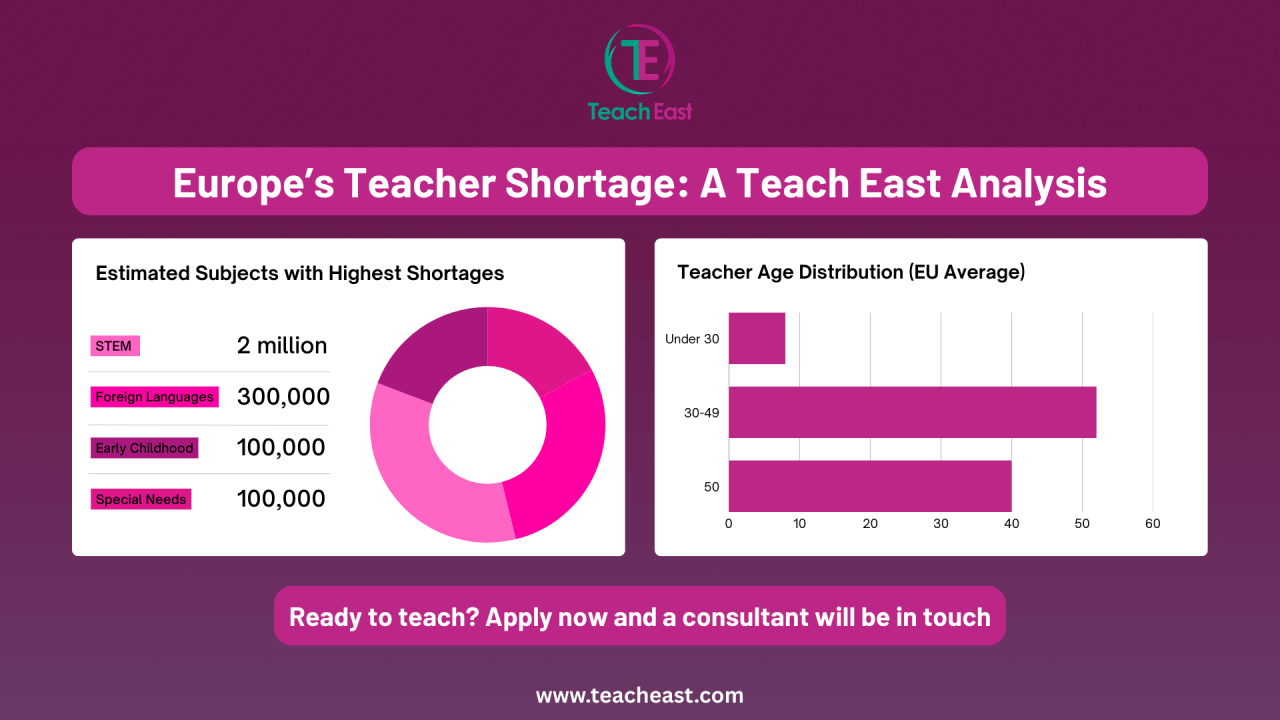

Teacher shortages are no longer an isolated challenge, they’re a crisis affecting almost every European country. In fact, by 2023, 24 out of the 27 EU member states reported difficulties filling teaching posts, with the pressure particularly severe in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) and foreign languages.

The consequences are not abstract. Schools across the continent are merging classes, reducing subject options, or hiring teachers without full pedagogical training. For students, this means fewer learning opportunities. For teachers, however, it signals a new reality: a profession in crisis that has become a candidate-driven market.

A Global Issue With a European Dimension

Globally, UNESCO estimates that education systems will need 44 million new teachers by 2030 to meet demand. Conflict, climate change, and population growth all play a role. In Europe, however, the shortage is magnified by very specific structural problems:

-

An ageing workforce:

Four in ten teachers are now over 50, while only 8% are under 30. In countries like Italy, Greece, and Lithuania, more than half of teachers are set to retire within 15 years.

-

Attrition and burnout:

High workloads and low recognition drive early exits. Many teachers leave the profession within five years, citing stress and lack of career progression.

-

Pay and status:

In Italy, teachers earn 27% less than other graduates. Across the EU, fewer than 40% of teachers report satisfaction with their salary.

-

Falling enrolment in teacher training:

Fewer young people are choosing teaching, deterred by its reputation for long hours and limited rewards.

Where Shortages Are Most Severe

Although shortages exist across the EU, certain countries and subjects are especially affected:

-

Germany

faces an acute gap of 240,000 STEM specialists, driven by digitalisation and climate protection targets.

-

France

has lowered qualification requirements, hiring graduates without full teacher training.

-

Spain

struggles with regional shortages, particularly in maths, physics, and English, while oversupply exists in other areas.

-

Ireland

reports persistent gaps in maths, science, and modern foreign languages, exacerbated by the cost of living in urban centres.

-

Nordic countries

including Finland, Sweden, and Denmark report severe shortages in early childhood education (ECEC), with Finland short by 6,000 preschool teachers in 2022 and Sweden projecting shortages in two-thirds of municipalities by 2035.

These are not temporary blips; they reflect structural imbalances that will deepen as current teachers retire.

Policy Responses: What’s Being Tried

Governments and the EU are attempting a mix of strategies:

-

Financial incentives:

Bulgaria, Czechia, and Germany offer salary bonuses, housing, or transport allowances to attract teachers to shortage subjects or rural areas.

-

Alternative pathways:

France, Belgium, and others allow subject graduates or native speakers to teach without traditional pedagogical training, a controversial but pragmatic response.

-

Professional development:

Erasmus+ Teacher Academies and national reskilling schemes allow teachers to gain additional qualifications in shortage subjects like ICT or maths.

-

Recruitment drives:

Several countries are subsidising tuition for students in teacher training, or promoting teaching as a career in national campaigns.

Yet challenges remain. Recognition of qualifications across borders is still inconsistent, limiting teacher mobility, even though the EU explicitly encourages it.

The Human Side: Why Teachers Leave

Beyond policy, the heart of the issue lies in how teachers experience their profession. Surveys consistently highlight:

-

High stress and workload:

EU teachers report some of the highest occupational stress levels compared with other professions.

-

Precarious contracts:

In Spain, Italy, and Portugal, more than half of teachers under 35 are on short-term contracts.

-

Low social recognition:

Fewer than 20% of teachers believe their work is valued by society.

This creates a vicious cycle: fewer young entrants, more attrition, heavier burdens for those who remain.

What This Means for Teachers

While the numbers paint a worrying picture for schools, they also signal opportunity for teachers. STEM specialists, language teachers, and early years educators are now in unprecedented demand. Rather than competing for limited jobs, teachers increasingly have the power to choose:

- Where in Europe they want to work.

- What kind of curriculum they want to teach.

- Which working conditions and benefits matter most.

How Teach East Supports Teachers

At Teach East, we recognise these shortages not as a distant policy problem, but as an opportunity to empower teachers. Our mission is to connect qualified European teachers with the schools that need them most, from STEM posts in Germany to early years roles in Ireland or language teaching in Spain.

We provide:

-

Access:

Opportunities across Europe you may not find alone.

-

Support:

Guidance on applications, interviews, and relocation.

-

Clarity:

Transparent information about salaries, benefits, and expectations.

Unlike agencies focused on bringing teachers from outside Europe, our strength lies in helping European teachers find opportunities within Europe, strengthening the profession while keeping talent within the region.

Conclusion: A Challenge, and an Invitation

Teacher shortages are not going away. If anything, they will intensify. But for teachers in Europe, this moment represents a turning point. Your skills are needed, and valued.

The question is not if there are jobs, but where you want to make your impact.

0 Comments